Forty years ago, three humans set out from planet Earth in a tiny capsule and headed for the moon. And 40 years ago tomorrow, two of them landed on its surface, got out of their spacecraft, and walked around a bit. To say it was an adventure would be akin to saying that the Himalayan Mountains are pretty tall hills.

Last Friday, I wrote about the quest for the moon, and some of the lesser-known challenges the NASA crews faced in trying to fulfill that quest, for The Atlantic Monthly. But no other venture I can think of epitomizes the notion of “No Map. No Guide. No Limits.” so well as that extraordinary exploratory feat. So I’m reprinting my Atlantic post here, in honor of the occasion. (The actual moon landing anniversary is tomorrow, but I’m posting this today because NASA is streaming a real-time replay of the Apollo 11 audio recording, even as you read this. So if you want to hear the actual voice transmissions between the Eagle, Tranquility Base, and Mission Control in Houston … and hear Neil Armstrong say “The Eagle has landed,” or “one small step for man …” see the link at the end of this post.)

So without further ado … my post:

It’s easy, once things become commonplace, to forget how extraordinary they once were. When Lindbergh flew to Paris, the whole world stopped to cheer. Now thousands of people jet back and forth everyday. Some 2,000 people have now reached the summit of Mt. Everest. And almost 500 people, from 39 countries, have flown in space. Which undoubtedly explains why I’m hard pressed to name even one of the astronauts who blasted off in the Space Shuttle Endeavor on Wednesday.

But every now and then, a moment catches us unaware, jolts us out of our complacency, and makes us feel the full wonder and impact all over again. I had one of those moments in 2002, when I spent a week covering a small sailplane event at Barron Hilton’s desert ranch in western Nevada. A dozen of the best sailplane pilots in the world were there, along with several of Hilton’s fellow aviation enthusiasts. And among the guests were two of the Apollo astronauts–Gene Cernan and Bill Anders.

One night, after our host had gone to bed, a small group of us took our drinks outside to look at the stars. Hilton’s ranch is in a remote valley, and he owns most of the land for miles in every direction. So the night sky was unblemished by human light.

For a while, we all just stared up at the sea of stars surrounding a partial moon. Stare long enough at a sky layered thick with stars, and you can get dizzy from the simultaneous closeness of their light and vastness of their reach. But after a few minutes, in the same way as someone might look at a photo of Rome and point out the hotel where they’d once stayed, Gene Cernan gestured to the moon and mentioned something about where, on that surface, he had been. He and Bill Anders compared notes for a minute. And then Cernan pointed to the left of the moon, to a star. “Hey,” he said. “And that’s … (whatever its name was).” He and Anders began pointing to and naming other stars. Someone in the group asked how they knew all those star names. “They’re the ones we steered by,” Cernan said, simply. And then to explain, as if he were giving a tourist directions to a local landmark … “you turn right at Maple, go straight until Main” … he gave us all directions to the moon.

What struck me most was that he talked about the route the way a local would, with a sense of familiarity about the twists and turns involved. And the star points with a casual ease of knowledge that no one who hadn’t been amongst them … detached from Earth, navigating across an unknown sea of space … ever could have mustered. With a sharp jolt, it hit me that I wasn’t just in the presence of NASA astronauts. I was in the presence of space travelers. Two of a tiny number of humans who had actually seen the Earth get small in the distance behind them, and then had to steer by starlight, across cold reaches of space, to find their way home again.

And in that moment, the Apollo program, and all that preceded it, became once again something breathtakingly astounding, wondrous, and surreal.

Looking back at all the celebratory news coverage, it seems almost a forgone conclusion that the moon program, and Apollo 11, would be successful. But behind that public end result was an extraordinary effort that reached so far beyond the possible or known that it easily could have … and perhaps by all Vegas betting odds should have … failed.

I have, in my office, a 10″-thick, 3-ring binder titled “NASA Launches Since 1958.” (A shorter summary version of it can be found here.)

It lists every launch NASA conducted, whether to test equipment, launch scientific instruments, or put humans into space. And it makes for fascinating reading. The main rocket booster for the Mercury program (the original astronaut effort) was the Atlas rocket. And from 1959-1962, more than half of the Atlas rockets (or Atlas combination rockets) NASA launched malfunctioned or exploded. One out of two. The failed rockets just didn’t happen to have people on top of them. One notable Atlas-Agena rocket booster malfunction resulted in its payload—a probe to get data about the lunar surface—missing the moon by a staggering 22, 862 miles and ending up in a solar orbit, instead. The understated comment in the “remarks” section notes “TV images were unusable.”

In the early days, communication systems were also limited and unreliable, requiring cumbersome back-up strategies and an extraordinary level of innovative thinking. On a test flight of the Saturn V vehicle that would launch the Apollo spacecraft, for example, the phone lines to the remote western Australia tracking station of Carnarvon went down. (NASA set up a worldwide network to keep track of the launches and keep in touch with the astronauts at all times.) Undeterred, the Australians sent launch times and data back and forth to the station over more than 1,000 miles of the Outback—using the top wire of cattle ranchers’ fences as a makeshift telegraph wire.

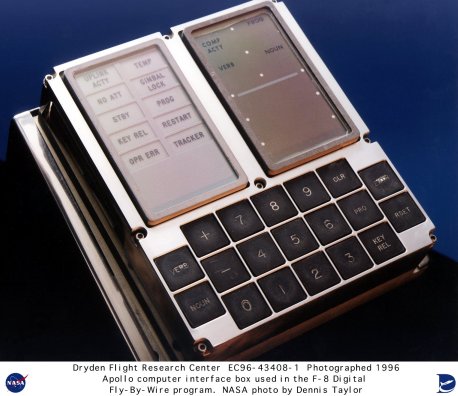

As for the high-tech systems that allowed the Apollo astronauts to operate their spacecraft and navigate to the moon and back … the Apollo computer was digital, but it had a whopping 36KB of memory. Think about it. We went to the moon on 36K. An email message can take up more computer space than that. On the plus side, the computer had a mean time between failures of more than 70,000 hours. (This reliability led NASA to later use the computer to control the first digital fly-by-wire aircraft without any mechanical back-up.) But because of the limited memory, the interface of the Apollo computer (shown below) was primitive. Every word command had a code number. So, for example, to open a valve, the astronaut would hit “verb,” then the number for the word “open,” then hit “noun,” then the code for the valve he wanted open, and then hit “enter.”

But wait, there’s more. That famous moon landing? The one where Neil Armstrong realized, as the automated landing system brought the lunar lander close to the surface of the moon, that the intended landing site was full of boulders, and so grabbed hold of the manual controls and hand-flew the lander to a better landing site, with only 30 seconds of fuel remaining when he landed? How did he get the confidence to do that at all, let alone the skill to do it so flawlessly? By flying this:

Officially called the Lunar Landing Training Vehicles, but unofficially called the “Flying Bedsteads,” these contraptions allowed the Apollo astronauts to practice free-flying a vehicle that behaved (through the ingenious combination of a vertically-mounted jet engine and numerous small jet thrusters) just like the lunar lander would in the low-gravity environment of the moon. The LLTVs were so squirrely and unstable that three astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, had to eject out of them when they went out of control. But Armstrong reportedly credited that experience with giving him the confidence to hand-fly the lander on the moon.

There are dozens and dozens more stories like these, tucked in the annals of NASA’s history books. But the point is, the moon landing wasn’t just remarkable because of its overall and lasting challenge. Viewed in light of how rudimentary our technology was at the time, and how many bullets we dodged—through innovative thinking, exhaustive effort, blissful ignorance, and pure, blind luck—the achievement becomes almost unbelievable. And yet, it happened.

On December 21, 1968, Bill Anders, Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, aboard Apollo 8, transformed the human race from a planetary species to a race of space travelers. And on July 16, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins set out to explore, on foot and in person, another body in the cosmos. We may do that again, and one day it may even become commonplace. But we will never again do it for the very first time.

In recognition of that fact, NASA is replaying the entire audio tape of the Apollo 11 mission, in real time, over the course of the next 7 days. You can tune into it here. And on Tuesday night, at precisely 9:56:20 pm Central Daylight Time, you can hear Neil Armstrong say, once again, “That’s one small step …”

Consider the obstacles. Consider the lack of knowledge and technology. Consider all that went wrong along the way. And then listen to the recording, in light of those reference points. And perhaps, if the stars line up just right, you might find yourself feeling the true wonder of it all—either for the first time, or all over again.

Next post: Does Emotionalism Help Entrepreneurs Succeed?

Previous post: What’s Next? A New Web Site Ponders the Answer

In 69 I was young. I had just started taking flying lessons.

I had grown up on a farm in Michigan. As a small kid I had layed out in fields watching planes fly in circles around our silo. Being dirt poor I never thought I would get to fly in a plane,let alone get a pilots license.

In 82 I realized that dream. It came about because of what Kennedy said,that we would put a man on the moon within the decade. Every time I think about the words that were spoken that night I get goose bumps.Thank you for bringing it back. Every time I set out on a trip, I am headed to the moon. Thank you, Art