More than once, I’ve said that the difference between a vacation and an adventure is that with a vacation, you know how it’s going to turn out. Of course, that also means planned trips can sometimes turn into adventures, if so much goes wrong that you’re no longer sure of how things are going to turn out.

When compared with flying into the Congo or getting stranded on a glacier, flying by airline from San Francisco, California to Providence, Rhode Island might not seem a likely set-up for new horizons or excitement. But last week, I was reminded once again that even standard, everyday life holds the potential for unexpected adventure.

My flight to Providence, on United Airlines, connected through Chicago. We were delayed taking off from SFO, but I had a 90-minute layover in Chicago, so all seemed fine. In fact, when the gate agent in Chicago came on board and informed us that they’d just had a massive thunderstorm come through, with 70-mile-an-hour winds, so lots of flights had been diverted to other airports (so we should check and make sure our connections hadn’t been cancelled), I thought the delay had been fortuitous. It had allowed us to miss the storm and land without being diverted elsewhere.

Walking through the Terminal C, I saw an ungodly line at customer service, hundreds of people long, that stretched halfway down the concourse—a result of all the diverted/cancelled flights. My connection, however, was scheduled on time, and all seemed right with the world … until it wasn’t. First, the Providence flight, coming in from D.C., was delayed because of the weather. Well, that was understandable. It landed, unloaded, and we were all about to board when they discovered a mechanical problem with the plane. Fifteen minutes later, the agent announced the flight was being cancelled.

From one of the spared to one of the condemned, just that fast. Some people dashed off for the lines immediately. But those of us who lingered a couple of minutes, contemplating our next move, got an invaluable tip from another gate agent who walked over about that point. [click to continue…]

So I was a little disappointed to discover, upon reading, that it was, instead, short answers from 12 people who do somewhat risky things, about why they do them. Which isn’t at all about why anyone “needs” risk. A more appropriate title might have been “Why I Think the Risk is Worth It.”

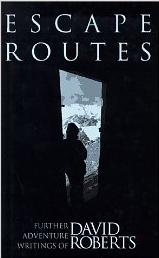

So I was a little disappointed to discover, upon reading, that it was, instead, short answers from 12 people who do somewhat risky things, about why they do them. Which isn’t at all about why anyone “needs” risk. A more appropriate title might have been “Why I Think the Risk is Worth It.” In the years since, Roberts has written for Outside, Men’s Journal, Smithsonian, National Geographic Adventure, and a host of other publications. And he is, indeed, one of the great adventure writers. But what makes me such a fan of his more recent writing is that it reflects that rare quality of a man who has mastered the art of growing up without losing the fire for life.

In the years since, Roberts has written for Outside, Men’s Journal, Smithsonian, National Geographic Adventure, and a host of other publications. And he is, indeed, one of the great adventure writers. But what makes me such a fan of his more recent writing is that it reflects that rare quality of a man who has mastered the art of growing up without losing the fire for life.