The motivating power of feeling as if what you do matters, and the collective power of working as part of a group, team, or community, are not new ideas. For years, I’ve had a little purple postcard posted to a bulletin board in my office with a quote by the anthropologist Margaret Mead that says, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” And in terms of the motivating power of purpose, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, more than 100 years ago, that “he who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” Come to think of it, as one of our guest essayists (Terry Tegnazian) wrote in her “I Do This Because …” post on this site, even the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead contained the prayer, “May I be given a God’s duty; a burden that matters.”

Humans are hard-wired to be working animals, and we do our best when we believe that our efforts matter. We’re also not well suited to be loners, despite the independent cowboy myth that runs through American culture. We get our greatest happiness, and also our greatest strength, from our connections with others.

Having said all that, the power of purpose and community are both huge subjects. So there’s always room for new perspectives, nuggets of information, or details on how those elements impact us. Take, for example, a recent study by a psychology researcher at the Yale-National University of Singapore. He wrote an essay about his results in The New York Times back in September. The piece was titled “Liking Work Really Matters.” But in reading it, I came to a different conclusion. It appears that the researchers looked at not just how enjoyable subjects thought a task would be (obviously, we focus better and do better at tasks we think are enjoyable), but also the impact on whether subjects thought the task at hand was important. And it’s the second part I believe is most important. [click to continue…]

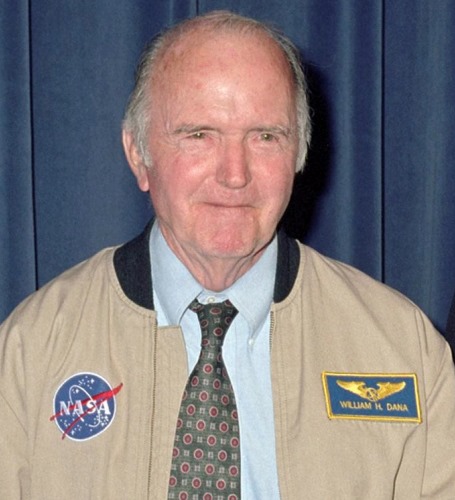

Ever since Tom Wolfe wrote The Right Stuff about those early Air Force test pilots who broke the sound barrier and went on to command the first missions into space, the American public has had a rather glamorized, Hollywood cowboy image of those dashing, daring young men who pushed our boundaries in flight and space outward.

Ever since Tom Wolfe wrote The Right Stuff about those early Air Force test pilots who broke the sound barrier and went on to command the first missions into space, the American public has had a rather glamorized, Hollywood cowboy image of those dashing, daring young men who pushed our boundaries in flight and space outward.