I just got back from a trip to the Middle East. My husband had been on a work assignment in Saudi Arabia for 18 months, and we decided to take some time to do some exploring in the region together (with our adult son) in between what was, and what is to be, in our lives.

Several people asked if I was going to post photos anywhere online, during the trip. I said no, and explained that in my 25 years as a journalist, even having to take my own photos for stories took away from my ability to be fully present where I was; able to immerse myself in an experience instead of thinking about how best to record it. To also focus on posting those images real-time would mean I’d have one piece of my brain back home at all times. Which means I’d miss a lot, including the focus, open-mindedness, and attendant opportunities for unexpected wonder and joy that come from being dis-connected from the noise of daily routine and life.

Focus is perhaps the most important part of that equation. New places and people and experiences can teach us a lot, but not if we’re always focused on ourselves: how we look, or what we’re going to show people back home. We need to look outward; connect, question, listen, look, and ponder what comes at us if we are to be changed by it. And that, to me, IS the point of exploring or traveling the world. To be changed. To see new perspectives, and experience and perhaps even understand things we have not encountered before.

Not that I haven’t ever taken a beach vacation just to chill and recharge. And I did take photos of us on the trip – all three of us love exploring the world, and I’ve found that when life gets hard, it’s good to have touchstones that help me remember the good times and laughter we’ve shared as a couple and as a family. Those smiles matter.

But what really struck me on the trip were the questions, thoughts, and sometimes-dizzying shifts in perspective that our travels encouraged (and, in some cases, forced) us to confront. Just a few:

1. Wadi Rum, Jordan

I’ve spent a lot of time in the southwestern and western deserts of the U.S. But the red sand and sandstone stretches of Wadi Rum in Jordan are far more wild, and less populated. Other-worldly enough that it made complete sense to us to discover that the movie “The Martian” was filmed there. Water is found in trickles, and yet Bedouins have lived and traveled there for centuries. How and why? The why is easier: it’s where they’ve always lived. It’s home. Same reason, I imagine, some people feel attached to the Mojave Desert of California, as barren and cold and blazing hot as that is. Of course, if you don’t control better land, your tribe doesn’t always have other options. And yet they survived here! Proof that humans are amazingly adaptable. But did there used to be more water? And therefore more options for goats or camels to graze? How has the world and the climate changed – not just in this century, but across time? As we sipped tea in a very hot, if shady, Bedouin tent, we were inspired to both ask questions and research the region’s history on our phones (modern travel!) And we learned that a trade route ran through here, and yes, there used to be more water. But still a dauntingly challenging existence, even with tourist money to supplement what the land offers today.

2. Petra, Jordan

Petra, Jordan, one of the 7 new wonders of the ancient world, is a mystery surrounded by an enigma, wrapped in a conundrum. Especially when you explore it with a son whose college major was ancient history with a background in archeology. Impressive ruins, for sure. With the remains of a columned street, amphitheater, and temples of a Roman city plunked down on top of a far more ancient … something. Gathering place? Sacred site? Winter home? Nobody really knows. Look at the detailed carvings in the temples carved into the rock walls of the canyon. Exquisite. Corinthian columns and figures and intricate designs. But the Nabataeans, the people who were known to live in that region when archeologists and historians theorize those mammoth carved buildings were created, were nomads. Why and how would nomads have either the engineering knowledge or the skill to build those kinds of structures? Not to mention the wherewithal, since the temples and carvings date back at least as far as the 3rd century B.C., during the bronze age, or the beginning of the iron age. Look again at the carvings. 150’ tall, with as much as 75’ of tall rock to be removed before the face of the temples is even begun. With bronze or iron tools? With that much detail and precision? I started developing a great idea for a novel about an pre-Greek empire Greek engineer who’d been to ancient Egypt (where there were Greek influences far back in time), who was either a restless soul or banished to exile in the Levant, and who then stumbled on a Nabatean tribe and fell in love with the tribal leader’s daughter, and won the father’s approval with promises of building him monuments of glory like other great leaders had. I’m kidding, but it’s not 100% impossible.

But the question remains … WHY? Culturally, nomads don’t build monuments and permanent structures. And then there’s the issue of water. Yes, there are impressive collection systems and cisterns there. But that wouldn’t get a large group of people through the many dry months when it’s well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Perhaps it wasn’t a permanent residence site (likely, for nomads), but an annual religious or tribal gathering place. But to invest decades (at a minimum) into carving structures and systems for a place you use only a couple of months a year? And why a massive temple structure 2.5 miles up in the mountains from the rest of the canyon? It doesn’t make sense! And yet, there it is, challenging and defying us to uncover and understand its story:

The iconic first temple at Petra, but far from the most interesting there.

Vivid layers of colored rock, with intricate carvings, with interior rooms 30’ tall and 60’ wide. Who would have done it, and why?

A close-up of one carved temple called the Monastery, because it’s 2.5 miles up a steep path from the other structures. Roughly 150’ tall and wide, set back 75’ into solid rock.

A broader view of the Monastery: 150’ tall, carved into a rock that required 75’ deep rock removal before the carving of the facade was even begun, 2.5 miles up a steep path from the rest of Petra, surrounded by such harsh landscape … why?

The ruins of an ancient Roman city on the valley floor, with the older rock-carved temples above them …

3. Egypt

And speaking of the challenges of uncovering history … We also spent time exploring the tombs and pyramids of Egypt, along with related artifacts now displayed in museums. Which led our son, the ancient history major, to ask if it was really morally defensible to desecrate tombs and pull out their contents to display, even for the sake of education and preservation? Especially in the case of Egyptians, who believed that if the body and goods were not left intact in the burial chamber, the owner would be kept from paradise and eternal life?

A challenging question that led to some really interesting family conversation. How would WE feel about having our parents’ graves dug up by curious people in the future? Worth noting is that most of the Egyptian tombs were raided by looters long before archeologists got to them. That’s why King Tut’s tomb was such a blockbuster discovery. It was intact. So if the goods are going to be raided by black market thieves anyway, preservation in a museum would appear to be a better choice. Like preserving an endangered species by capturing and housing surviving examples in a protective enclosure. But it doesn’t remove the discomfiting realization that it is still an intrusive and morally murky action, especially when it comes to sacred burial sites:

The pyramids at Giza.

A burial chamber inside one of the Great Pyramids in Giza.

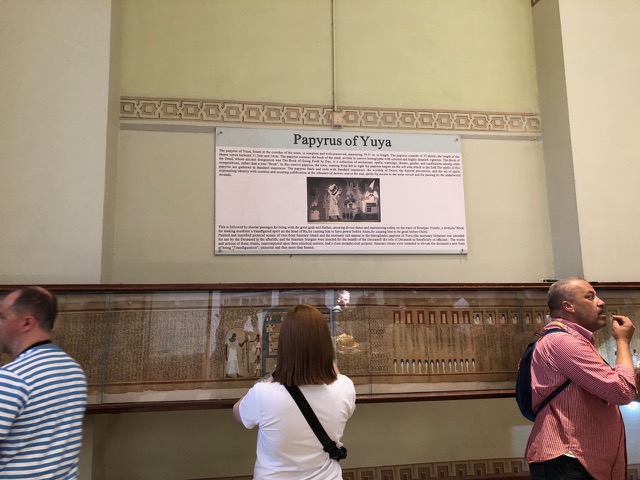

Papayrus taken from one of the many tombs archeologists have uncovered and whose contents have been removed for display.

4. The Limits of Our Perspective

And finally, we found ourselves, as so often happens in international travel, coming face to face with the limits of our protected, American perspective. For example:

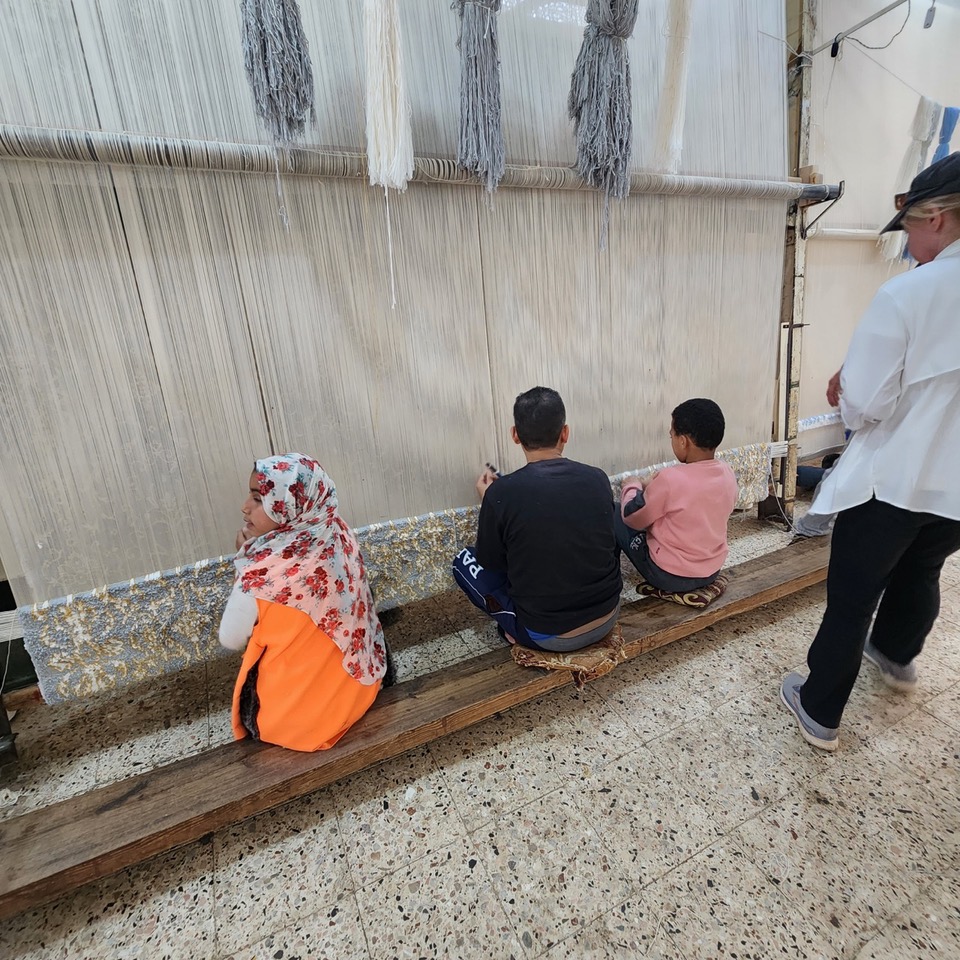

We spent a couple of hours at a national government carpet school near Saqqara, Eqypt, where children are learning the ancient trade of making Egyptian carpets by hand. They spend the morning learning to make, and making, carpets. After lunch, they get classroom lessons in Arabic, English, math, etc. And they get paid for the time they spent working as apprentices in the rug factory on the lower floor of the school. Looked at through an American idealist’s eyes, it is, inarguably, child labor. But to get to the school, we’d just driven through miles of a mentally overwhelming montage of trash heaps, polluted canals, rubble-strewn half-finished buildings and shacks, all screaming unbearable poverty and squalor. What would the better alternative be for poor kids in a country where school is not free, and many families don’t have the money to school or feed regular, good, lunches to their children? They’re not going to play on nice playgrounds after school, with snacks provided by the PTA. Ever. And looked at through that lens, these kids are at least learning a trade they can use to feed themselves, while learning to read, write, do math, and be fed at least one good meal a day. We have no idea how good our options really are.

Children learning the trade of rug-making at a government-supported carpet factory and school.

Or, finally this, below: a photo of us and our guide at Saqqara. On one level, a nice tourist photo. But spending the day with her, we learned a lot. And not just about ancient history. She explained that she had a PhD in Hieroglyphics, which made her incredibly valuable as a guide, since she could translate what we saw on monuments and papyrus rolls. But it begged the question: What was a woman with a PhD doing working as a tour guide? Hints arose. She talked about her daughter, who, at the age of 16, participated in the 2011 protests in Tahir Square – and, as a result, had been arrested by the police. Her daughter was then tortured and repeatedly gang raped by the police for the next six months before her mother finally was able to get her released. Just digest that for a moment. It’s one thing to know that inhumane torture exists in the world, and that women are often the victims of violent sexual assault as a threat or punishment for speaking up. It’s another entirely to spend a day with an anguished mother who has first-hand experience with it. Our guide also talked about knowing the only five Jewish people in Egypt – all women, and all of whom kept their religion a secret, for fear of reprisal. Was she being literal and serious? I don’t know. But we got the point. And I was humbled by the courage of a woman who moved in those circles, had a PhD but worked as a tour guide, and was still standing tall after enduring all that she talked about, and all that she surely left unsaid.

Travel beyond what we know is important. But to reap its full rewards, we have to be open not only to the moments of beauty and wonder, but also to being discomfited, unsettled, and changed by our experiences. And to have that happen, we need to look outward, and seek all that places have to teach us, show us, or even shock us with. To savor the beauty, yes, and rejoice in the sense of wonder and discovery they help us find again. But also to be challenged to rethink things; to expand our understanding and beliefs; to feel things we don’t, at home. Those moments are as important as the beauty; the memory of the dark that highlights the precious value of the sun. And if we’re lucky, we return home with more than cool photos. We return home humbler, wiser, and more grateful for all that we have.